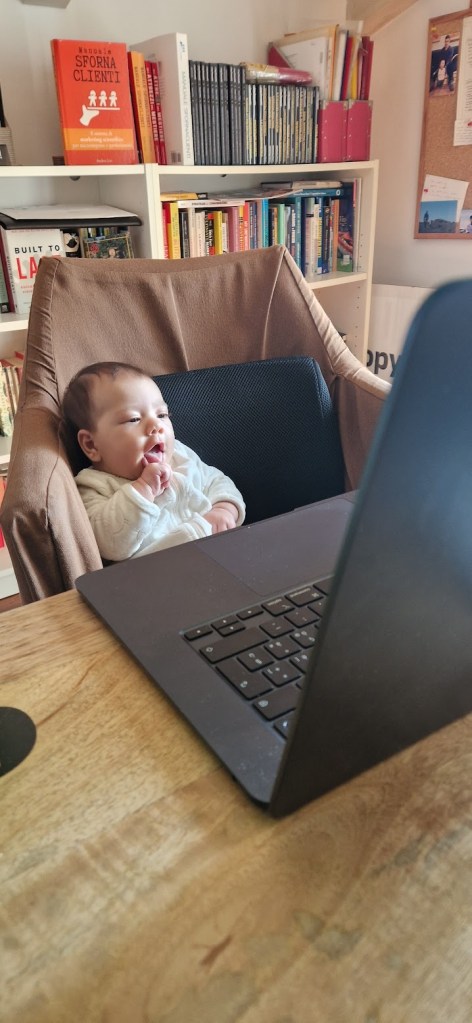

As a father of a nearly five-year-old (Mauro) and a newborn (Luce), I’ve been thinking a lot about what it truly means to guide children without controlling them.

This reflection led me to explore the ideas behind “The Sovereign Child,” a philosophy that radically shifts how we see kids, learning, and authority.

I encountered the concept through a recent Tim Ferriss Podcast episode featuring Naval Ravikant and Aaron Stupple.

After listening, I put Aaron Stupple’s book on my to-read list. While I wait to dive into it, I’ve jotted down a few early reflections.

From Empty Vessels to Fellow Explorers: Children as Knowledge Creators

At its heart, this philosophy stands on one powerful truth: children aren’t empty vessels waiting to be filled—they actively create knowledge, just as we adults do. When I watch my son construct his understanding of the world, I see not a passive student but a fellow explorer.

The parent’s role shifts dramatically here. I’m not the director of his learning but its supporter. Not a gatekeeper but a facilitator.

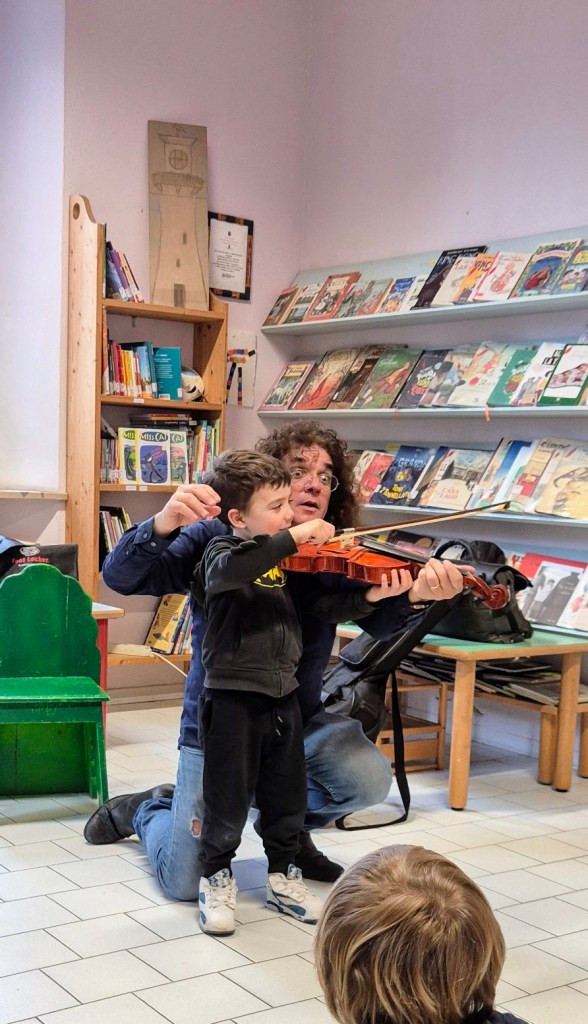

This realization hit home recently with Mauro, who’s still in preschool and doesn’t read yet. I caught myself trying to push him into tracing letters, hoping he’d “get ahead.” But he resisted—and it quickly turned into tension.

So I stepped back. Instead, I started writing notes and drawing near him, just for fun. Before long, he came over curious, asking what I was doing, wanting to try. His interest grew—not because I pushed, but because he saw me enjoying it.

Every time we force a child to do something, we unintentionally position ourselves as adversaries. It’s better to approach it in a sweeter manner. Every moment of resistance can become not a battle to win but an opportunity for creative problem-solving together.

This shift in perspective naturally leads to a fundamental revaluation of what drives genuine learning.

Following the Snail: The Gold of Genuine Interest

One concept that fundamentally altered my approach is the supreme value of interest. A child genuinely captivated by something—whether it’s carnivore plants, space, or how washing machines work—has found the true fuel of learning.

Last month, my 4-year old became obsessed with snails in our garden. Rather than pulling him away to complete a planned “educational” activity, I followed his lead. I watched as he uncovered one big snail under a rock, measured it, talked about their species. That night, we picked up and read a wonderful book in English named “The Snail and the Whale”. I can’t say how many skills he developed through this organic exploration, but I figure it will surpass what I could have done by programming.

The point is that where traditional education often treats interest as a distraction from “important curriculum,” this model inverts that thinking: interest isn’t just important—it’s essential.

Beyond Rules: Building Knowledge

Another key distinction lies between rules and knowledge.

Rules exist in isolation; knowledge creates coherent frameworks.

My parents and grandparents believed that you must follow rules, for rules’s sake. There was no such thing as “sweet discipline”. Many times, when I questioned some order and asked “why?”, they answered “Because I say so”.

What did that teach me? To despise all authority, to avoid its controls, regardless of the reason why certain rules existed.

What I listened in the podcast reflects exactly my experience with Mauro. When he first understood why we wash hands—the actual concept of germs and how they spread— he started doing it on his own. And sometimes, after dinner, he’s the one who prompts me to get up from the sofa and go brush our teeth together.

He doesn’t just mechanically follow a handwashing or teethbrushing rule. Since he got the “why”, through patient persuasion and example, he connected this knowledge to other situations. Now he understands why, for instance, we shower and why food safety matters.

Breaking Cycles: Our New Approach to Parenting

Following Paola’s lead, I now believe in having and following few basic disciplines. We learned this from several sources, some of which are the most famous Maria Montessori, as well as Tracy Hogg.

We believe kids need (and crave) limits. These have to be few, to not end up making your kids feel like they’re in prison. But we make these limits clear and enforce them. For instance, no one is allowed to “alzare le mani”, i.e. to beat anybody. And for me this has been an important detachment from the violent tradition I grew up in my family of origin.

Paola did not experience any of that, and she grew fonder of rules (maybe also because her dad was a judge?). As a new parent, 4 years ago, I started to cope with “automatic” acts of violence and authoritarian approaches that I displayed every time Mauro did something I deemed wrong.

When faced with the frightening thought that I was repeating the same mistakes I blamed on my family of origin, another emotion followed: shame.

I had to meditate and talk a lot about what I’ve been through. Now, as an accomplished adult, it’s easier than ever before. And I thank my wife and children for the growth opportunity they provided. It all started with accepting the facts: I suffered physical beating and verbal humiliation as a kid and teenager.

Inside me, I had already forgiven my parents. I have empathy for them as people, grown up as they were in a different era, less informed and often under stress for their own jobs and responsibilities. And I’m grateful for all the good things they gave me (subject for another essay or memoir).

Nonetheless, recognizing what we did not want to replicate was the starting point to develop a new, self-directed approach to parenting.

Me and Paola did a lot of research since deciding to become parents a couple years ago. It’s clear that the old approach was harmful. We decided to do things differently and try to avoid mistakes that were made with us in the past.

While this journey feels deeply personal, I thought about how these ideas have deeper historical roots than the modern podcasters suggested.

From Francisco Ferrer to Naval Ravikant: The Radical Roots of Self-directed Education

This isn’t new thinking.

While the podcasters referred to these ideas as born in the US a couple decades ago, I first heard them in old European libertarian books.

When I was 16, indeed, I discovered the Spanish educator Francisco Ferrer. He founded Spain’s “Modern School” in 1901 on similar principles: no punishment, no coercion, child-led discovery. He believed traditional education served as social control. And he was executed because of his ideas.

In many ways, The Sovereign Child approach echoes that same radical freedom: raising independent thinkers rather than followers.

As both an entrepreneur who values independence and a father who values connection, this is the legacy I want for my children—not perfect obedience, but the courage to think for themselves in a world that increasingly demands conformity.

Cultural Differences: European vs American Parenting

Me and Paola went to high school together and discovered how disastrous it is to force kids to memorize facts.

Of course, we had some good professors, that pushed us to be critical thinkers. But I gotta admit: my emphasis on understanding underlying principles began outside public school or university.

And as for our children, we’re very happy about the preschool system here in our region (Emilia-Romagna). The level is high, as they get many stimuli, play and socialize a lot.

But when they turn 6 they’re destined to go State school, and I do not expect them to learn much useful there. Here in Italy (and Europe in general) there’s no such thing as “homeschooling”, let alone “unschooling”.

It’s true that the US were founded on a much deeper respect for the individual, and these cultural differences have a big impact. What makes me look at the future with peace of mind, though, is the fact that our children will grow up as digital natives.

While this raises many issues, it’s undeniable that they get access to an infinite pool of free knowledge. Something that we, born in the late 80’s, could only dream of.

It was in fact 2002 when I first “searched” something on the internet, precisely anarchist publications such as the ones mentioned above. Of course, the web is more complicated and full of trash nowadays. But, as a father, I trust my leadership and their curiosity to use it in a productive way.

Despite these cultural constraints, we’re finding ways to apply the philosophy’s most valuable principles in our daily parenting decisions.

The Uncomfortable Freedom: Practical Applications in Daily Life

The “Sovereign Child” philosophy manifests in concrete, often controversial practices:

Food: “Children should have unlimited access to food,” Naval explains on the podcast. He shares a striking anecdote: “One parent I know let their child pour out all the lollipops on the floor. The kid ate about 20 of them, got bored, and moved on.” The theory isn’t that children always make perfect choices, but that experience itself becomes the teacher.

I grew up in a family-owned cafe, with candies and pastries everywhere. I ate like a pig during most of my childhood, and I managed to stay in good shape only thanks to a lot of sport. So I do not feel like I’m the right person to stop my children.

Of course I want them to eat as healthy as possible. My wife’s a doctor, and she basically solved the issue by removing most junk food from the house. She also did a great job selecting fresh fruits and vegetables for Mauro since the time she stopped breastfeeding him.

In this realm, he’s a pretty normal child. He likes chocolate, but he knows he can have it in small portions and mostly dark. He discovered sugar when he was 2 years old. Once a week, he gets gelato, even in wintertime (it’s a huge tradition here in Ravenna for all kids when parents come pick them from school). But he also loves avocado and often enjoys Roman cabbage.

Generally speaking, since we live in Italy and not the US or UK, we’re not much concerned. As of this writing, Paola is still breastfeeding Luce. But when she turns 6-7 months, we’ll begin the process again: proposing her good nutrient foods first, just like we did with her brother.

Then, if they want to try “spazzatura”, I’ll be the first to say “try it and see how it makes you feel”.

Screen Time: The podcast guests advocate for unrestricted access here as well. “What we call ‘addiction’ is often misleading,” they argue. “Children’s interests naturally evolve. Today it might be cartoons; tomorrow it could be coding or documentaries.”

When Mauro’s home on weekends and I want to write, some cartoons on YT Kids or Disney+ or Netflix are my solution. Besides that, we usually have a more rigid approach:

- Mauro does not own an iPad and is not allowed to touch any of our smartphones

- He can only watch cartoons before dinner (for maximum 1h) or after lunch in the weekends (2h maximum)

We prefer to read him books, of which we always have plenty (bought, gifted of borrowed for free from the amazing local public libraries). Or we play, both cardgames inside and basketball or else outside.

Sleep: “There’s no fixed bedtime in our house,” one speaker shares. “We simply dim the lights, go to bed ourselves, and let natural rhythms take over instead of enforcing artificial routines.” The approach trusts children to recognize their own tiredness cues.

As far as we are concerned, it’s all about routines. From Sunday night to Thursday night, we try to have dinner early (around 7.30 pm). After that, Mauro has always spent some time with us, and then one of us accompanied him to bed and read him ONE single story. Nowadays, with Paola breastfeeding Luce, Mauro usually goes to bed with me – almost never later than 9.30 pm.

Learning: Naval distinguishes clearly between unschooling and homeschooling: “Homeschooling still follows a curriculum. Unschooling is entirely interest-led and self-directed.” Studies mentioned in the discussion suggest unschooled kids can catch up academically in just one year when needed, but more importantly, their motivation comes from within.

Problem is, I couldn’t find any source for those studies. And in Italy, as already mentioned, homeschooling is considered very weird. Most people don’t even know that it is an option. I only remember a no-vax community in the Trento region making the news during the pandemic for developing “clandestine schools”.

And as for unschooling, it is considered a violation of our “right to study” – something belonging to an old era of widespread illiteracy. Nowadays, kids dropping out of school is deemed a serious issue. It’s especially relevant in Sicily or other regions, where it reached 17% in 2023.

My view on this? I respect and admire the individualistic spirit of the US Constitution. As an entrepreneur, I prospered by breaking the rules and trusting I could do better than the norm. So I’m not against either homeschooling or unschooling. But I live in Italy, and here the culture is a little different, as already mentioned above.

So far, with Mauro in a very kids’ friendly preschool and Luce yet to enter it, I have not experienced any damage or disadvantage for them joining State education. An entrepreneur friend whose son has almost finished Liceo Classico (same kind of high school I did), confirms the bad news: it’s outdated and it forces kids to memorize useless info. Even worse, it makes the kids lose interest in learning.

What about private schools? They are no better. The ones in Ravenna are all catholic. And if there’s one thing we fear more than the State, it’s religion. So that is not an option either.

Sibling Conflict: “Don’t jump in to force apologies or sharing,” the speakers advise. “Conflict is essentially boundary negotiation. You intervene to stop physical harm—but allow emotional expression and natural problem-solving.”

So far, we only have observational evidence from our friends with two kids (a rare species nowadays). We spent lots of time with a couple who has two males. The second kid was born two years after the first, and their parents embraced a very curated but “hands-off” approach, with minimum control. Almost never raising their voice nor trying to give them many limits.

When hanging out with them, we were pretty scared half of the time. The two kids were seriously trying to harm each other, and it was hard to stop them. Especially the oldest one, looked like he just couldn’t stand the younger and wanted to kill him. After a couple years, things turned for the better. But I remember thinking that if they were my kids I would have been much more stern and harsh.

However, that’s precisely the point Stupple makes. And I’m curious to see how Mauro and Luce will negotiate their own boundaries going forward.

Ownership: The podcast emphasizes clear ownership over forced sharing: “This toy belongs to you. You can trade it or lend it—but you don’t have to.” This approach builds respect and negotiation skills rather than resentment.

I like that idea. I’m used to see family as a “commune”. After all, even many right-wing people agree that that’s the only place where Communism can work. Thus, we usually call the house “our house”, even though Mauro and Luce are currently users and heirs, rather than owners :)

Jokes aside, there is not much scarcity here. We have plenty to share, and only want our kids to show thrift and responsibility, We consider these high and non-negotiable values. For instance, I always let Mauro notice when he forgets some light on after leaving a room, because I don’t like waste.

One basic foundation of the household is that each member of the family has his or her space and things, that no one is supposed to take – at least not without asking for consent. Pretty easy, right?

And finally, main decisions are taken by adults. We don’t want to end up like some friends, who are actually slaves to their children, because they let them dictate everything. But we are careful to always ask first “what would you like to eat?” or “where would you like to go today?” and try to satisfy their wishes. If requests are unfeasible, we then negotiate a more reasonable solution. And that’s how they’re supposed to relate between themselves.

Wild Animals or Free Thinkers? Addressing the Criticisms

Stupple and Navikant’s parenting style naturally attracts criticism. No rules on sleep, food, screens, or school? Many call it irresponsible or indulgent. Some dismiss it as a privilege only certain families can afford.

Naval joked that his sovereign-raised children were “closer to wild animals than properly raised children.” While provocative, this comparison contains wisdom: animals in their natural habitat display innate intelligence and appropriate behavior without external control systems.

Critics often ask: “But how will they function in the real world?”

The answer is pointed: they’re already living in the real world—one where consequences flow naturally from choices, not from arbitrary authority. The controlled environments of traditional schooling and parenting are the artificial constructs.

A statement that particularly resonates with me:

“I’d rather my children be disobedient, free, and unpolished than obedient and well-behaved.”

Having grown up in Italy’s education system and then breaking free to build my own path as an entrepreneur, I’ve seen how genuine resilience springs not from structure but from passion. When my son becomes obsessed with something—whether it’s poking bugs in a puddle or mastering any detail about tens of dinosaurs —he’ll work persistently through frustration. That’s where true grit develops.

Moving beyond the theoretical debates, I’ve been developing specific strategies tailored to each of my children’s developmental stages.

Practical Applications for My Children

For my soon to be five-year-old:

- Cultivating autonomy: Instead of answering every “why,” I’m learning to ask, “What do you think?” or “Should we discover it together?”

- Meaningful choices: “Do you want to put on your coat before or after your shoes?” This builds decision-making muscles without overwhelming.

- Co-planning: “We need to visit grandma today. Should we go in the morning or afternoon?” Being included in planning builds investment.

- Introducing “chosen rules“: Like those in a board game—vs. imposed rules.

For my infant:

- Speaking with respect—even when she doesn’t understand the words, she reads tone and intention.

- Observing natural rhythms for sleep and feeding rather than imposing schedules.

- Creating rich environments: Different textures, sounds, and safe exploration spaces.

For both:

- One-on-one time: Blocks of unstructured time with each child individually.

- Honoring emotional reality: When jealousy or frustration emerges, I’m learning to let it exist without immediately trying to fix or suppress it.

Of course, translating philosophy into daily practice is where the real challenge begins…

Implementing This in Real Life

This isn’t an overnight transformation. It’s a mindset shift requiring energy, especially during challenging moments. Naval’s advice resonates with my entrepreneurial approach: start small, experiment during your strongest times of day, iterate based on results.

This aligns perfectly with my concept of high-leverage parenting: identifying the small changes creating the greatest impact. It’s how I’ve built businesses, and now, how I’m building my family culture.

My wife and I have started “trial days” where one leads with sovereign principles while the other observes. We’re not dogmatic about methods—we’re curious about outcomes.

What do you think?

I’m sharing this journey as it unfolds, not as an expert but as a fellow parent finding my way.

Have you experimented with any aspects of the “Sovereign Child” approach? What challenges have you faced balancing freedom with necessary guidance? Do cultural expectations in your country shape your parenting decisions?

Whether you’re skeptical of these ideas or already implementing them, I’d love to hear your experiences. Parents learn best from each other, especially when navigating approaches that differ from how we were raised.

If this stirred something in you—wait till you read the next part. I dive deeper into how we’re applying these ideas day by day, with all the tension, joy, and mess that come with real-life parenting.

👉 Read part 2 here

4 thoughts on “Life as a Dad: Raising Sovereign Children? [Part 1]”