Vai in più basso per leggere l’originale in italiano.

PART I – THE ROOTS (1954-1970)

In the first episode we witnessed Osvaldo’s dramatic entrance into the world. In the second one, we discovered his wild adventures as a child and boy in Gaeta during the Fifties and early Sixties.

Now it’s time to delve into Isabella’s origins. The narration continues in my father’s voice.

Isabella’s birth and childhood

From Sora to Gaeta

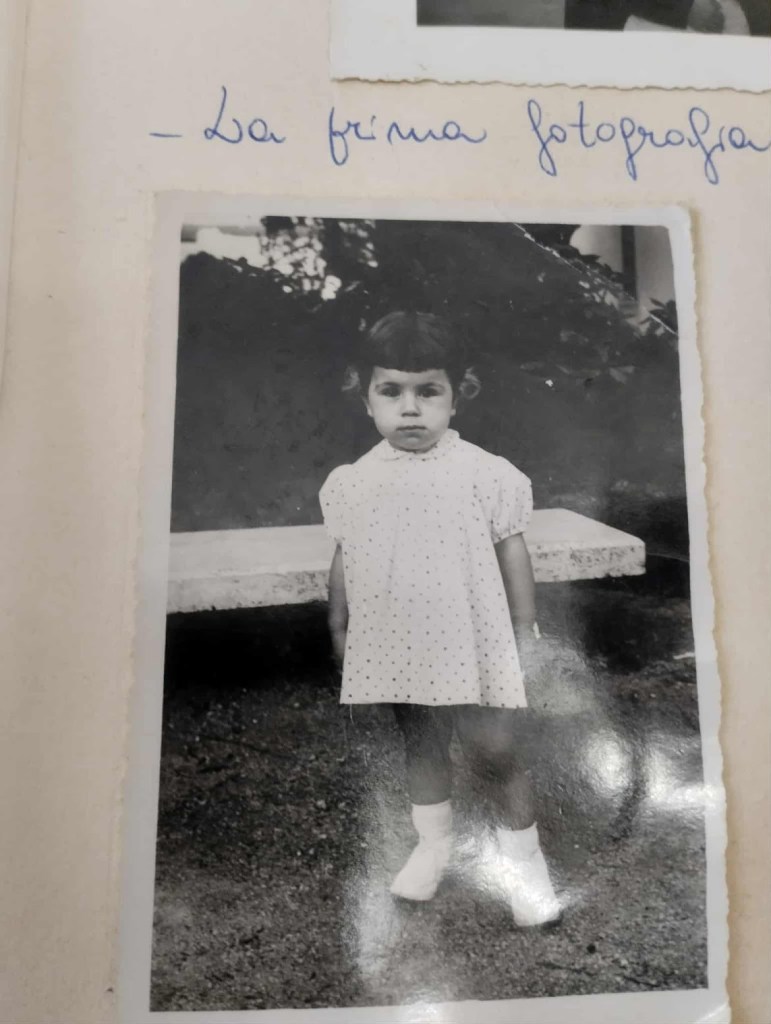

Isabella was born on November 6, 1957 in the Ciociaria area – about three years after me. But she was my opposite. Where I ran around and caused chaos, she stayed quiet. She observed. A child who seemed afraid of her own breath.

They lived in Sora, on Via Conte Canofari, a dirt road that led to the cemetery. Countryside all around, houses scattered like missing teeth in an old mouth. Today there’s an entire new neighborhood there, but back then it was all different. Packed earth. Dust that rose with the passage of carts.

Her parents, Loreto and Lina, both from the Abruzzo region, had married recently. They had spent three beautiful months in Anzio, in a small house on the beach. Then he, a finance officer, had been transferred to Sora. In 1955 Franca was born, the older sister. Two years later came Isabella.

Loreto traveled the countryside for tax inspections. He knew all the farmers, helped them even with bureaucratic paperwork. A just man, Isabella always told me. One who believed in rules but had an open heart.

In Sora the air was heavy. The surrounding mountains trapped everything. Summer worse than in Abruzzo, winter froze your bones. A place that tightened your chest even when there was no fog.

The smell of wax

Isabella’s ordeal began at six years old. Elementary school with the nuns.

“Not the good school where Franca went,” she told me that evening. Her voice had grown lower. “The one for good families. No. I ended up in the other institute. The strict one.”

The smell of wax in the corridors. Forty children crammed into a classroom with a single teacher. Sister Vincenza.

“She must be almost a hundred now, if she’s still alive,” Isabella added. Her eyes fixed on emptiness.

The long canes on the desk. Crack. They would cane you on the palm of your hand, not the back. Where it hurt more. Where the skin is thin and the nerves scream.

“Turn your hand over, Isabella.”

And she obeyed. Always. Because she was afraid.

A boy with a piece of ear torn off. Another with a broken finger. Sister Vincenza didn’t limit herself to the canes. Perhaps she thought that was the right way to educate. Or perhaps she had forgotten what it meant to be a child.

Isabella never spoke. She was closed like a shell. When they questioned her she felt like vomiting. Literally. In the morning, before leaving the house, her stomach would turn from tension.

“There was another girl who vomited like me,” she told me. “But that one was the daughter of a famous lawyer. They treated her with every consideration. They beat me.”

The panettone

She was given consideration for only one week. When they brought a panettone from the barracks. Lina had said: “Oh well, take it to school.”

For seven days Isabella had become “the favorite.” Then the panettone ran out and so did the teacher’s sweetness.

The queen without a crown

When Isabella was eight years old, Grandmother Elisabetta died, Loreto’s mother. A woman who had blue blood in her veins but dirt under her nails. Daughter of counts and dukes ruined by the Avezzano earthquake. She had married for love with a peasant and had lived in poverty, but she treated everyone with the dignity of a queen.

At her funeral there was the whole town. Even the neighboring one.

“I was shocked,” Isabella told me. “I didn’t know all those people knew her and loved her.”

From that day on she couldn’t study anymore. She remained traumatized. Lina would find her sitting in front of books but the words confused themselves, slipped away like water on glass. She didn’t understand anything anymore.

At school things got worse and worse. Sister Vincenza caned her more.

“You don’t study, Isabella. You don’t speak. What do you want to do when you grow up?”

She didn’t know. She only wanted to disappear. To become invisible like the dust that settled on the desks.

Franca’s shadow

In first grade of middle school they sent her to the school where Franca went. Finally. But the comparisons began. Franca was one of the best in the class. Isabella wasn’t. She was the one who never spoke up. The one who lived in her sister’s shadow.

The Italian teacher terrorized her. “She was like an SS sergeant,” Isabella told me, and when she used those words I understood she wasn’t exaggerating.

She would call her for questioning and she would freeze. Her tongue glued to her palate. Her heart beating so hard it hurt.

One day the teacher called Lina. She told her she was failing Isabella. That she wasn’t cooperative.

And here Isabella smiled at me, for the first time during that whole story.

“Mom got angry,” she said. “Really angry.”

Lina had looked that woman in the eyes. “Look, Isabella talks at home. Isabella studies. Isabella knows things. Maybe you’re the one who isn’t capable. And you shouldn’t make comparisons with her sister. Franca is Franca, Isabella is Isabella.”

That sentence had saved her. It had made her understand that she didn’t have to be like her sister. She had to be herself.

But Sora felt increasingly tight for her. On the positive side, Loreto had become known and loved in the countryside. At Christmas and Easter they were buried in local cheese wheels, loaves that smelled of wood and fire, little gifts. Lina sewed, kept the house, raised them with patience.

Then everything changed.

The list

September 1969. Isabella was almost thirteen years old. Loreto had to be transferred. First to Narni, a tiny town in Umbria where the air was bad. But Lina wasn’t well during that period. She had a nervous breakdown. She hadn’t recovered from the death of Grandmother Elisabetta and the loss of the third child, who had died shortly before birth.

“We need the sea,” Loreto had said. “Clean air.”

He had written a letter to the ministry explaining the situation. He had requested a city on the coast.

The list arrived. Gaeta was the first choice. Gaeta with the sea, but also with the military prison. At the time it didn’t have a good reputation. “They’re sending you to Gaeta” wasn’t a compliment. It was a threat.

But Lina had heard “sea” and immediately said yes.

Loreto had come to Gaeta alone to look for a house. He couldn’t find anything, especially because of the dog. That dog had become the third child, he always took it hunting. But in the end he had to give it away. Isabella never told me, but I understood that too had been a loss.

He had found an apartment on the top floor of a building on Via Serapide. As it happens, right above where one day our first bar would be. Destiny plays strange tricks sometimes.

The sea washes everything away

“September 29, 1969,” Isabella told me. And she remembered the exact date, as if it were yesterday. “We arrived in Gaeta by taxi. Me, mom, and Franca. The luggage seemed too little for an entire life.”

She had climbed the stairs of that house. The apartment on the top floor, at the corner. The windows opened onto a different horizon. The air smelled of sea. Of salt. Of freedom.

For the first time in years she had breathed.

“It will be different here,” Lina had told her, and she had believed her.

Because in Gaeta there was the sea. And that, as she would discover later, washes everything away. Even fear. Even silence.

Isabella raised her eyes and looked at me. “I discovered it three years later,” she said. “When a boy asked me to dance. And I, for the first time in my life, said yes.”

That boy was me.

And in that moment, sitting at the kitchen table with the now-cold cup of coffee between her hands, I understood why Isabella was the way she was. Why sometimes she needed silence. Why certain words cost her effort.

And I also understood that that “yes” said to a shy boy like me, so many years ago, had been her first act of courage.

The first of many.

To be continued…

Subscribe to follow along or check back regularly to read the next installment.

Copyright © Andrew Lisi

Nel primo episodio abbiamo assistito all’ingresso drammatico di Osvaldo nel mondo. Nel secondo abbiamo scoperto le sue folli avventure di bambino e ragazzino a Gaeta durante gli anni Cinquanta e l’inizio degli anni Sessanta.

Ora è il momento di approfondire le origini di Isabella. La narrazione continua nella voce di mio padre.

Nascita e infanzia di Isabella

Da Sora a Gaeta

Isabella è nata il 6 novembre 1957 in Ciociaria, circa tre anni dopo di me. Ma lei era l’opposto del sottoscritto. Dove io correvo e facevo casino, lei stava zitta. Osservava. Una bambina che sembrava avere paura del proprio respiro.

Abitavano a Sora, in via Conte Canofari, una strada sterrata che portava al cimitero. Campagna tutt’intorno, case sparse come denti mancanti in una bocca vecchia. Oggi lì c’è un intero quartiere nuovo, ma allora era tutto diverso. Terra battuta. Polvere che si alzava al passaggio dei carretti.

I suoi genitori, Loreto e Lina, entrambi abruzzesi, si erano sposati da poco. Avevano vissuto tre mesi bellissimi ad Anzio, in una casetta sulla spiaggia. Poi lui, finanziere, era stato trasferito a Sora. Nel 1955 era nata Franca, la sorella maggiore. Due anni dopo Isabella.

Loreto girava le campagne per i controlli fiscali. Conosceva tutti i contadini, li aiutava anche con le pratiche burocratiche. Un uomo giusto, mi ha sempre detto Isabella. Uno che credeva nelle regole ma aveva il cuore aperto.

A Sora l’aria era pesante. Le montagne intorno intrappolavano tutto. D’estate peggio che in Abruzzo, d’inverno ti congelavi le ossa. Un posto che ti stringeva il petto anche quando non c’era nebbia.

A scuola di severità

Il calvario di Isabella è iniziato a sei anni. Le elementari dalle suore.

«Non nella scuola buona dove andava Franca,» mi ha detto quella sera. La sua voce si era fatta più bassa. «Quella delle famiglie bene. No. Io sono finita nell’altro istituto. Quello severo.»

L’odore di cera nei corridoi. Quaranta bambini ammassati in un’aula con una sola maestra. Suor Vincenza.

«Deve avere quasi cent’anni ora, se è ancora viva,» ha aggiunto Isabella. I suoi occhi fissi nel vuoto.

Le bacchette lunghe sulla cattedra. Crack. Ti bacchettavano sul palmo della mano, non sul dorso. Dove faceva più male. Dove la pelle è sottile e i nervi gridano.

«Gira la mano, Isabella.»

E lei obbediva. Sempre. Perché aveva paura.

Un ragazzino con un pezzo d’orecchio staccato. Un altro con un dito rotto. Suor Vincenza non si limitava alle bacchette. Forse pensava che quello fosse il modo giusto di educare. O forse aveva dimenticato cosa significasse essere bambini.

Isabella non parlava mai. Era chiusa come una conchiglia. Quando la interrogavano le veniva da vomitare. Letteralmente. La mattina, prima di uscire di casa, lo stomaco si rivoltava per la tensione.

«C’era un’altra bambina che vomitava come me,» mi ha raccontato. «Ma quella era figlia di un avvocato famoso. A lei facevano tutte le accortezze. A me davano botte.»

È stata presa in considerazione solo una settimana. Quando hanno portato un panettone dalla caserma. Lina aveva detto: «Vabbè, portalo a scuola.»

Per sette giorni Isabella era diventata “la preferita”. Poi era finito il panettone ed era finita pure la dolcezza della maestra.

La regina senza corona

Quando Isabella aveva otto anni è morta nonna Elisabetta, la madre di Loreto. Una donna che aveva avuto sangue blu nelle vene ma terra sotto le unghie. Figlia di conti e duchi rovinati dal terremoto di Avezzano. Si era sposata per amore con un contadino e aveva vissuto in povertà, ma trattava tutti con la dignità di una regina.

Al suo funerale c’era tutto il paese. Anche quello vicino.

«Sono rimasta scioccata,» mi ha detto Isabella. «Non sapevo che tutta quella gente la conosceva e la voleva bene.»

Da quel giorno non riusciva più a studiare. Era rimasta traumatizzata. Lina la trovava seduta davanti ai libri ma le parole si confondevano, scivolavano via come acqua sul vetro. Non capiva più niente.

A scuola andava sempre peggio. Suor Vincenza la bacchettava di più.

«Non studi, Isabella. Non parli. Cosa vuoi fare da grande?»

Lei non lo sapeva. Voleva solo sparire. Diventare invisibile come la polvere che si posava sui banchi.

L’ombra di Franca

Alla prima media l’hanno mandata nella scuola dove andava Franca. Finalmente. Ma sono iniziati i paragoni. Franca era una delle più brave della classe. Isabella no. Era quella che non interveniva mai. Quella che viveva nell’ombra della sorella.

L’insegnante di italiano la terrorizzava. «Era come un sergente delle SS,» mi ha detto Isabella, e quando ha usato quelle parole ho capito che non esagerava.

La chiamava per interrogarla e lei si bloccava. La lingua incollata al palato. Il cuore che batteva così forte da far male.

Un giorno l’insegnante ha chiamato Lina. Le ha detto che bocciava Isabella. Che non era collaborativa.

E qui Isabella mi ha sorriso, per la prima volta durante tutto quel racconto.

«Mamma si è arrabbiata,» ha detto. «Si è arrabbiata davvero.»

Lina aveva guardato quella donna negli occhi. «Guardi che Isabella a casa parla. Isabella studia. Isabella sa le cose. Forse è lei che non è capace. E non deve fare paragoni con la sorella. Franca è Franca, Isabella è Isabella.»

Quella frase l’aveva salvata. Le aveva fatto capire che non doveva essere come sua sorella. Doveva essere se stessa.

Ma Sora le andava sempre più stretta. Di positivo c’era che Loreto si era fatto conoscere e voler bene nelle campagne. A Natale e Pasqua erano sommersi di caciotte nostrane, pagnotte che sapevano di legna e fuoco, regalini. Lina cuciva, teneva la casa, le cresceva con pazienza.

Poi tutto è cambiato.

La lista

Settembre 1969. Isabella aveva quasi tredici anni. Loreto doveva essere trasferito. Prima a Narni, un paese piccolino dell’Umbria dove l’aria era brutta. Ma Lina in quel periodo non stava bene. Aveva un esaurimento nervoso. Non si riprendeva dalla morte di nonna Elisabetta e dalla perdita del terzo figlio, morto poco prima di nascere.

«Abbiamo bisogno di mare,» aveva detto Loreto. «Di aria pulita.»

Aveva scritto una lettera al ministero spiegando la situazione. Aveva chiesto una città sulla costa.

È arrivata la lista. Gaeta era la prima scelta. Gaeta col mare, ma anche col carcere militare. All’epoca non aveva buona nomea. «Ti mandano a Gaeta» non era un complimento. Era una minaccia.

Però Lina aveva sentito «mare» e aveva detto subito sì.

Loreto era venuto a Gaeta da solo a cercare casa. Non trovava niente, soprattutto per via del cane. Quel cane era diventato il terzo figlio, lo portava sempre a caccia. Ma alla fine l’aveva dovuto regalare. Isabella non me l’ha mai detto, ma ho capito che anche quello era stato un lutto.

Aveva trovato un appartamento all’ultimo piano di una palazzina in via Serapide. Guarda caso, proprio sopra dove un giorno ci sarebbe stato il nostro primo bar. Il destino gioca strani scherzi, a volte.

Il mare lava via tutto

«29 settembre 1969,» mi ha detto Isabella. E ricordava la data esatta, come se fosse ieri. «Siamo arrivate a Gaeta in taxi. Io, mamma e Franca. I bagagli sembravano pochi per una vita intera.»

Aveva salito le scale di quella casa. L’appartamento all’ultimo piano, all’angolo. Le finestre si aprivano su un orizzonte diverso. L’aria sapeva di mare. Di sale. Di libertà.

Per la prima volta da anni aveva respirato.

«Qui sarà diverso,» le aveva detto Lina, e lei le aveva creduto.

Perché a Gaeta c’era il mare. E quello, come avrebbe scoperto dopo, lava via tutto. Anche la paura. Anche il silenzio.

Isabella ha alzato gli occhi e mi ha guardato. «L’ho scoperto tre anni dopo,» ha detto. «Quando un ragazzino mi ha chiesto di ballare. E io, per la prima volta in vita mia, ho detto di sì.»

Quel ragazzino ero io.

E in quel momento, seduti al tavolo della cucina con la tazza di caffè ormai fredda tra le sue mani, ho capito perché Isabella era così. Perché a volte aveva bisogno di silenzio. Perché certe parole le costavano fatica.

E ho capito anche che quel «sì» detto a un ragazzino timido come me, tanti anni fa, era stato il suo primo atto di coraggio.

Il primo di molti.

Continua…

Pubblicherò un capitolo alla volta nei prossimi mesi, condividendo la storia dei miei genitori mentre la scrivo e la raffino.

Iscriviti per seguire o torna regolarmente per leggere la prossima puntata.