When in 2003 I first read about Lamb of God in an obscure Italian magazine, I did what people intrigued by new music did back then:

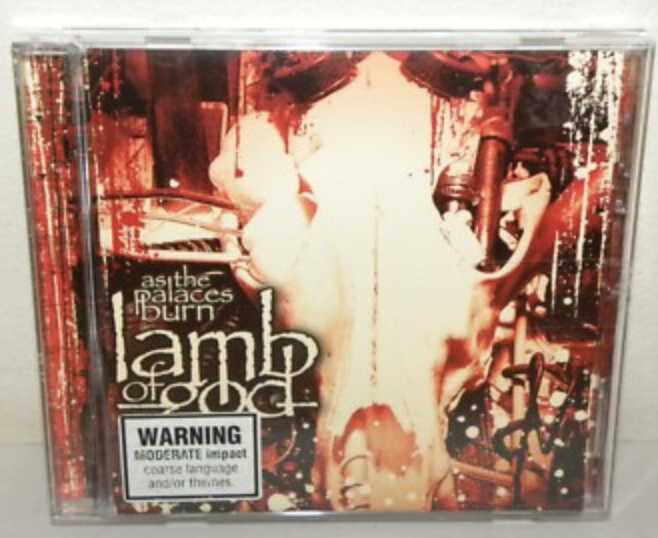

I went straight to my local record store and ordered the CD — As the Palaces Burn.

It may sound laughable to younger folks, but it took weeks to arrive. And when it finally did, the first listen hit me like having my brain and skin scraped by a giant rusty cheese grater.

For context, I was around sixteen and still coming from the nu-metal era — Korn, Mudvayne, that kind of thing. The most violent record I’d owned up to that point was probably Slipknot’s Iowa (which already felt shockingly extreme back then).

Only years later did I realize that much of that abrasive, collapsing-building sound — the one that really made you feel the title As the Palaces Burn — came from another mad genius I would grow to admire deeply, both for his music and his production style: Devin Townsend.

That was my introduction to extreme metal — the real kind.

The kind played by people who actually knew how to perform fast and fierce.

It vaguely reminded me of Megadeth and Metallica, but more aggressive.

A bit like Slayer, only without the dumb lyrics — and with a voice that actually drew you in.

Words Like Fire

As an avid reader, passionate about literature and philosophy, vocalist in a few teenage bands, and writer of songs, poems, and self-printed fanzines about Nietzsche and Poe, that was the part that fascinated me most:

Randy Blythe’s lyrics and voice.

The songs’ words — and that very image of palaces burning and collapsing — hit me with the same force as the ending scene of Fight Club.

And the voice was the first form of growl or scream that truly dug into me and conquered me, even though I wasn’t used to that kind of furious expression.

I have to admit, after Ashes of the Wake I stopped following them – just like I did with most metal. The passion only came back recently, thanks to the sheer convenience and abundance of music catalogs, interviews, and behind-the-scenes content I now find on Spotify and YouTube.

I did what I often do these days: I bought a T-shirt or some other piece of merch — my way of supporting artists whose work and image still resonate with me.

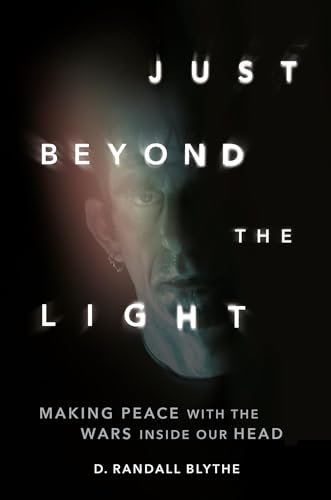

Then, like many others, I got curious about what Randy had been publishing. Not his earlier bestseller about his time in prison , but his more recent collection of essays and personal stories, Just Beyond the Light.

It’s not journalism, and not quite just a memoir. It’s not fiction either, yet I kept turning page after page (or rather, scrolling through it). This notwithstanding being even admittely full of very long sentences.

Seeing it recommended by people like Mark Manson and other podcasters and writers who popularized a no-nonsense approach to philosophy only deepened my curiosity.

I’m genuinely glad these two interests, once belonging to completely separate eras of my life, have finally converged: my teenage immersion in extreme music, and my adult fascination with self-development.

Actually, the lack of personal growth in most of my friends and idols – along with the apparent inextricable link to drugs and alcohol – were the main reasons I cut ties with the metal (and rock) scene in 2012.

Whiskey, Walls, and Wake-Up Calls

Similarly to some stories Randy recounts in this book, I ended up drinking whole bottles of whiskey every single time I played. Even at concerts where I was the main producer (and then I had to go on stage and perform). Also at rehearsals or when seeing other bands play. Heck, I was fucking drunk on a daily basis.

One night, after a show I did play at Sinister Noise in Rome (legendary venue that used to exist in the Garbatella neighborhood) I apparently went around knocking walls and shops’ serrande, then almost fell off a bridge. My friend and guitarist Luca rescued me just in time. The morning after, I woke up in the proverbial pool of vomit and blood. That was the first turning point for me.

Yes, I kept drinking in the following years, but much less (just “socially”, as many people say). It went on until one famous podcast episode by Andrew Huberman persuaded me to eventually quit completely. And I’ve bee totally alcohol-free since.

Unlike Randy, I never touched cocaine (except one night as a kid when a friend, again a musician, after my repeatingly saying no, tricked me by passing a joint with very little white powder on it – which fortunately just made me raise my head from the sofa and stay awake a little longer. For the substance effect and for the rage against the guy). I never even became addicted to tobacco, even though I occasionally bought and smoked some until I was a 20-year old.

During lockdown, I started growing some weed. When I became a father for the first time I quit. But other friends kept gifting me some. And in the meantime, I bought shares of a CBD company. So that became my latest vice, even though I never really liked smoking. This, though, I’m still grappling with.

“Being around negative, fucked-up people is like squatting in a Boston alleyway dumpster in February—you’re gonna start stinking and catch a cold.”

That line makes me think about the many people who live cannabis almost like a religion. Sometimes we had much fun sharing a joint, but I remind myself I don’t need THC to escape stress.

It’s not just about substances; it’s about proximity — who and what you let into your mental space.

Sobriety, in that sense, isn’t only about abstinence. It’s about curation: choosing what kind of energy I keep around.

Lately, that means more solitude, more music, and fewer conversations that drain me.

The Stoic and the Scream

Since 2013, I totally transformed my life. But it took some radical moves (changing place, friends, books, clothing style, many habits, and yes, even music).

Now I do consider myself successful. But how can one shut down an entire part of himself that way? For little more than a decade, I was only involved in getting my Master’s degree, then my first real jobs outside of the family cafe, and then building my own businesses and family.

At the time it felt like the right thing to do. I’ve always been radical, all-in or all-out type. So I stopped screaming and sold most of my instruments, along with tens of t-shirts and CDs (As the Palaces Burn is among the few that I kept).

Beneath the noise, the chaos, and the addictions that haunted so much of the metal world, there was a quiet awareness. I sensed that my artistic drive alone wouldn’t take me far. I lacked the skill, and I knew it. I could either surrender completely to the art — study, practice, embrace it as my main identity — or redirect my energy toward something that might actually lead somewhere.

This entailed struggling with my ego. For years I couldn’t go see any concert, because I was too envious of whoever was on stage and was pursuing that dream. I was still enraged with myself.

But I lived a lot in the meantime. I gave all myself to the ventures I engaged since. One common element to how I approached music is the entrepreneurial spirit. After less than a year as an employee I quit looking for a job. I stopped trying to fit in. Like I did with my bands and publications before, I wanted to create and manage it in my own way.

Choosing to work remotely in 2015 was still a totally counter-intuitive choice. As it were to become a freelance and at the same time choosing a field – copywriting – where I had zero experience and few in the Italian market even knew what it meant.

Seeing how some of these experiences are mirrored in Randy’s book gave a deeper meaning to some advice one may read in many other videos or books on the same subject.

Like many others, I guess, I found value not just in the philosophical ideas presented in Just Beyond the Light, but in how Randy did his own hero’s journey to discover their truth and apply them in his own life.

And of course, there is the emotional connection I felt since the beginning, which made me buy the book in the first place.

As for the Stoics, I enceountered them in high school, and again years later — when I started reading them in Italian with the Latin or Greek texts side by side. I definitely don’t need a contemporary American guy to explain Epictetus, Marcus Aurelius, or Seneca to me.

But it does make me happy to see this philosophy treated in a mature, sharp, and still rebellious way — as Randy, or rather D. Randall Blythe, does.

The Day Light Was Born

Earlier this year my daughter was born. Her name is Luce — which, in English, literally means Light.

Since then, everything has started to shift.

What once felt urgent — work, growth, numbers, even visibility — began to lose gravity.

I didn’t foresee a crisis; it simply arrived with her, quiet and blinding at the same time.

The same word that now fills my home with warmth is also the title of Randy’s book: Just Beyond the Light.

And maybe that’s not a coincidence.

Maybe it’s a reminder that every birth, literal or creative, illuminates the edges of our previous life — and makes what used to matter seem suddenly small.

Curiously enough, this commentary is as much about the light as seeing. And one of the first songs I wrote in my life was called See the Light.

“Art is the outwardly manifested expression of the artist’s search for meaning.”

That line hit me harder than any technical definition ever could.

Because that’s exactly what I’ve been doing — through journals, spreadsheets, audio notes, articles, newsletters and the endless daily act of trying to make sense of things.

All of it has been an attempt to externalize the search for meaning, to turn confusion into structure, noise into signal.

“Art is an expression of imagination perceptible via our senses that conveys a truth about the human experience.”

Because at a time when, professionally and financially, I’ve reached a level I couldn’t have imagined only ten years ago, I find myself going through a crisis in which art has once again become my anchor.

A crisis of meaning, indeed.

“It is within the often-painful experience of the artistic process that the artist attempts to understand both themselves and the world around them.

Art is the outwardly manifested expression of the artist’s search for meaning.”

I found myself thinking: maybe that begins where the numbers end.

Where the act of seeing regains its urgency.

Where craft becomes a mirror, and expression becomes a way of staying alive. Truly mindful of the apparent lack of sense in most of human activities. Alive as the small flickering light we represent in the vastness of the universe.

“This ability to communicate that view is what we call talent, and that’s all artistic talent really is: the ability to effectively communicate ideas in a particularly focused specific form.”

While I re-read this, synchronicity wanted me to hear about the new LoG song, Sepsis:

Many metalheads are criticizing it. Many others, like me, still mourn the departure of founding member Chris Adler, who was at the center of the unique sound the band introduced over 25 years ago.

But I must say, I like the bass vibe and the sludgy-doomy riffs. And as well, the vocal style (even though, since I now know Randy can actually sing, I would expect some clean vocals as well, maybe in the other songs of the next album?).

This new song, anyway, shows a lot of talent and a very nice rawness. Once again, I feel proud of Randy, Mark and the guys for bringing this kind of in-your-face art to the masses. After all, they’re signed to a major label, have played the biggest venues worldwide and contributed to raising the bar in mainstream music.

Yes, as a fan who discovered them over 20 years ago when they were still underground, I feel their success is somehow the success of people like me.

Speaking of which, I absolutely adored that chapter in the book where Randy speaks of “his people”. My only regret is that I would have enjoyed it and used it and cherished it much more 20 years ago. And in case my own son and daughter will feel like that when growing up, I’ll go back to this book and have them read it as well.

The Discipline of Seeing

“I have come to understand that this is my function, the function of the artist—to simply notice what is already there and shine a light so that others may see it.”

When I read that line, it felt like Randy was describing the very reason I started writing novels, and also reopened this blog.

Not to build a personal brand or produce “content,” but to document the practice of seeing — to record how awareness sharpens through discipline and through living.

I had actually started OcchiPerVedere (Eyes to See) back in 2009, inspired by another great lyricist and extreme music frontman: Barney from Napalm Death. Even then, the impulse was the same — to look at the world harder, to write my way toward clarity.

In a sense, that’s what I’ve been doing ever since, without calling it art: tracking time, writing my quarterly reports, refining systems, optimizing work. It was all an attempt to “shine light” on the invisible structure of my own mind.

Now I see that the same instinct. Once it was meant to gain business clarity and lifestyle “optimization”. Currently, I feel more energy should go to assembling a body of literary work. Where my imagination, interpretation and ideas shape stories in which people can see themselves and find their own meaning.

Art as the Discipline of Staying Awake

“Musician wants—no, needs—to make music, and a real musician makes music whether people like it or hate it.”

It’s not about the money or status when you do this (there are far easier ways to get a very good income and even build wealth). For me, it’s about expressing and perfecting a craft. Maybe giving others relief, just as that form of art gave you relief. And, most certainly, it’s about having no regrets.

I seriously ponder death, memento mori. Thus I want to reach that end point (be it in decades, or tomorrow, or later tonight) with the satisfaction of having finished the projects I started. Or, at least, I want to feel no remorse about having chosen to live the way I wanted to.

— around 1305 he painted a haunting vision of Hell where the devil devours souls.

Yes, he was paid to do that, but he put all his medieval meditations on sin and fear into it, including extraordinary details and even some Pope’s punishment. And he changed the way people painted from then on

“Don’t sit around agonizing over whether the imaginary art you haven’t made yet is gonna be any good, just start doing it.”

That’s the challenge I wrote to myself just yesterday: what the hell am I waiting for?

I’ve built the conditions for freedom — time, space, money — and still find excuses not to create.

These lines cut through all that.

Maybe the point isn’t to find more motivation or validation, but to return to the simplest impulse: do the work because it’s the only thing that feels alive.

“Once the final draft has been edited and sent off to the printers, I will feel a brief moment of great satisfaction… then the creeping dread of emptiness and lack of purpose will begin to grow.”

Just as he can’t stop creating, going from one project to another, I’ve been called “obsessed” by many, my wife and parents included. Because every time I reached a new goal or completed a big project, the normal response is – understandably, from those who love you – to tell you to “cool down” or “take a break”.

Like, in 2023 I was totally new to real estate, but I invested a huge sum first in learning, and then lots of time and even more money into buying and renovating not one, but two apartments in a row. It was exhausting at the time, and people around were concerned by the risk and involvement I displayed. But now both I and my family get to enjoy the fruits, as I became financially free.

And for instance, I recently started writing a memoir of my parents and grandparents as well as a new novel. I do this while I’m writing other books for clients, running a marketing agency and raising two children. I don’t need to do all that (except being a father). So I definitely feel that this urge to create something from nothing is as much a curse as it is a blessing.

“You have to have the guts and be willing to put a huge chunk of yourself into the work if you want to create something new—this is the only way.”

Maybe that’s what this whole year has been about: rediscovering the point of doing anything once the practical reasons fade.

The real work now isn’t to make more, but to see more.

And perhaps, after all the spreadsheets and quarterly analyses, I’ve come back to the same place I started — not to accumulate, but to perceive.

Art, then, is the disciplined act of staying awake.

“There are no guarantees in music or any other form of art… this is a pirate’s life.”

That’s the reminder I needed most.

After years of chasing predictability, I forgot that uncertainty was what made the early days exciting.

Freedom, like art, isn’t safe.

It’s a sea you learn to sail, not a system you optimize.

“Maybe no one will care about your ideas… It doesn’t matter, though, because it is through this search, the artistic process, that we learn how to see and come to know ourselves.”

I think that’s what this last year has been about — rediscovering the point of doing anything when the practical reasons fade.

The real work now is not to make more, but to see more.

And maybe, after all the spreadsheets and quarterly analyses, that’s the function I’ve been circling back to since the beginning: not to accumulate, but to perceive.

Art, then, is the disciplined act of staying awake.

“Using AI, that terrifying engine of banalization and intellectual decay, to instantly produce art doesn’t make anyone an artist either—there is no process.”

I smiled when I read this.

I’ve been using AI daily — to do complex marketing research, automating workflows, editing tens of thousands of words of copy, analyze numbers, and even my own thought and decision patterns. It’s been liberating in practical terms. But Blythe’s words reminded me of the line I drew: AI is fine for business, not for my art.

Because art, to me, isn’t about efficiency. It’s about friction — about staying in the ring long enough to bleed a little and come out seeing differently.

Maybe that’s why I’ve been drifting back toward music and writing: because they demand me, not my systems.

It takes me hours to write articles such like the one you’re reading. It took me years of study and then hundreds of hours to actually finish my first novel. I even got into a legendary fight with my wife because of that, since when she was pregnant with Mauro I looked more intent on my drafts – and respecting the deadlines I gave myself – than anything else.

The point of it all? The same one Blythe highlights. Pushing yourself, fighting the Resistance (to quote the War of Art) and eventually putting all you got into that final piece, which (we like to think) will last forever.

When the Noise Becomes the Message

“Even though we cannot eradicate fear and anxiety from our lives, it helps to know their source… echoes from a time when the stakes were much, much higher.”

I felt this in Venice last week, walking among the crowds, fighting the claustrophobia that hits me in places full of noise and faces.

It’s not fear of people, but of losing boundaries — of dissolving into the swarm.

Reading Blythe’s words reminded me that anxiety is ancient, biological.

There’s nothing wrong with feeling it; it’s a leftover survival instinct in an overstimulated world.

Also, I’m an introvert and I’m aware that being around too many people – especially if I did not chose them – it’s a huge drain. Randy’s book, as much as his music, is about not fitting in with the crowd – and the fact that it’s ok. It’s also a reminder that someday, somewhere, you will find your crowd. The one where some like-minded weirdos gather.

Recognizing that helps me breathe again — literally, and metaphorically.

That, we must recognize, is the best part of living in the digital age. On the other hand, it looks like something has broken.

I mean, I was some kind of spammer when I used to log on MySpace to let people know about my band’s new EP and live shows. But it was productive. And most importantly, it only lasted for the 2 hours I had payed. [Smartphones hadn’t been invented, I did not own a laptop, and had to actually walk everyday to the local Pakistani-owned internet point].

So what the fuck is going on in the Instagram and Tiktok era?

“An aggressive cult of toxic narcissistic individualism has grown way out of control.”

“It’s all just noise, and paying attention to that crap… is a complete waste of time.”

That’s exactly why I no longer post on social media.

I don’t want to scream into the algorithmic void, or fight to be seen by people who aren’t even looking.

I’d rather build a quiet corner of the internet that still feels like a room — OcchiPerVedere as a sort of monastic cell where I can write to think, not to perform.

Because as Blythe says, most of what passes for communication today is noise. And it’s way more disturbing than some heavy guitars and drums blasting from the speakers.

Silence, or selective attention, has become an act of rebellion. It takes a contrarian mind to try and build a deep life.

“I don’t ‘belong’ anywhere on the internet. I belong here, in the physical world, with people I can hug and look in the eye.”

This line nearly made me laugh.

After years of digital networking, automations, and perfectly calibrated campaigns, I feel exactly that.

Belonging happens in the real world — in the kitchen with Paola, in the park with Mauro, when Luce laughs. I belong with actual friends I can meet around the corner in my neighborhood here in Ravenna, or take vacations together.

And even though he speaks at his younger audience, I find Randy’s right. It’s useful for everybody to remember that none of what people “comments” under some video or post can actually hurt you. It’s not real.

“Kid, take that feeling of being other… and own it. That thing that makes you feel so different is a superpower if you use it correctly.”

When I reconnected with extreme metal this year, that teenage feeling of being “the odd one” came back — and I welcomed it. Yes, you can be bullied or excluded from some circles.

But if you can channel it, that outsider energy that made you feel isolated can become your greatest asset. You have got have the guts to embrace it, though.

I’m proof that if you dare to be different and original, that is valuable. Critical thought, courage and a good taste will serve you well in a world of copycats.

“Somebody has to stand tall and proud, to show the next generation of oddballs and rejects that despite the whole world trying to knock them down just for being themselves, there can be no surrender and there is no giving up—that somebody might as well be you.”

One thought on “Art and the Search for Meaning – A commentary on D. Randall Blythe’s “Just Beyond the Light””